Introduction

In the pursuit of enhanced patient safety, Barcode Medication Administration (BCMA) systems have emerged as a pivotal health information technology. Celebrated for their potential to significantly reduce medication errors, these systems automate the critical verification process, ensuring the ‘five rights’ of medication administration are meticulously followed: right patient, right medication, right dose, right route, and right time.1 By scanning barcodes on both medication and patient identification wristbands, BCMA provides nurses with an invaluable tool for real-time validation, directly addressing the serious consequences of medication administration errors.3 The healthcare sector has broadly embraced BCMA, with hospitals worldwide investing heavily in its implementation.4–7 Studies have consistently demonstrated BCMA’s effectiveness in lowering medication administration error rates and mitigating harm from severe mistakes.8 Furthermore, BCMA adoption has been linked to improved patient identity verification rates, reinforcing its role in bolstering safety protocols.9 10

Despite the proven benefits and over two decades of availability, integrating BCMA seamlessly into existing hospital infrastructures has presented considerable challenges.5 11–15 Research underscores that the implementation process itself is a critical determinant of BCMA’s ultimate success.12 13 Paradoxically, some studies have reported increased workload and workflow disruptions associated with BCMA use, leading to the development of workarounds.7 12 14 16 17 These deviations from policy, often manifesting as practices like precanning medications on carts,18 can inadvertently introduce new error pathways, potentially negating the intended safety advantages of the technology.7 12 18

While the existence of BCMA workarounds and policy deviations is acknowledged in prior research,7 12 18 the underlying reasons for these deviations and the influence of contextual factors remain underexplored. A systematic review focusing on BCMA’s impact on patient safety concluded that human factors and technical limitations are significant barriers to achieving optimal scanning rates and realizing the full patient safety potential.1 Another review echoed these concerns, emphasizing the importance of examining deviations beyond the traditional five medication error types, as these may also carry significant safety implications.19 Therefore, this study aimed to delve into nurses’ practical interactions with BCMA technology, specifically focusing on identifying policy deviations as indicators of potentially unsafe practices through a human factors lens.20 The core objectives were threefold: (1) to gain an in-depth understanding of nurses’ actual BCMA usage during medication rounds, (2) to quantify and categorize BCMA policy deviations during both medication dispensing and administration phases, and (3) to analyze the root causes of these deviations in relation to the socio-technical dynamics of the work environment.

Methods

Study Design

This study employed a concurrent triangulated, mixed-methods approach, combining structured observation (quantitative data) with field notes and nurse commentary (qualitative data) to comprehensively analyze BCMA utilization across two medical wards within a 700-bed hospital in Norway. Structured observation, facilitated by a digital tool, provided quantitative data on policy deviations. Concurrently, field notes and nurses’ comments contextualized the quantitative findings, offering explanations and insights into the causes of observed deviations.

Theoretical Framework: SEIPS Model

The Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model16 20 provided the theoretical framework for this research. This model is instrumental in examining the complex interplay between humans, technology, and the environment within a work system. It has been successfully applied to studies of medication administration technologies16 and across various healthcare settings.20 In this study, the SEIPS model served as a framework to categorize integrated qualitative and quantitative data according to its five core elements:20 (1) tasks, (2) organizational factors, (3) technology, (4) physical environment, and (5) individuals. This holistic approach allowed for a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing BCMA policy deviations.

Setting and Context

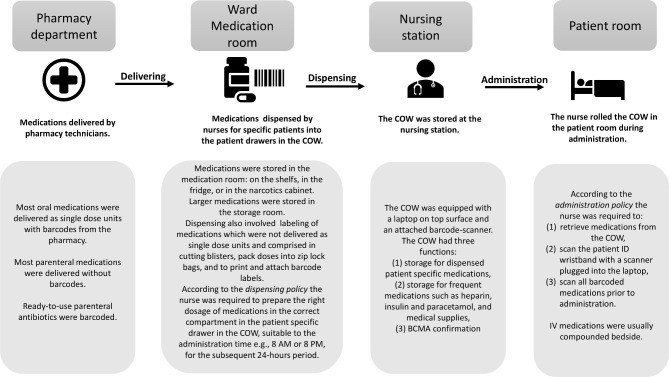

The study was conducted at a hospital that pioneered the implementation of electronic Medication Administration Record (eMAR) and BCMA technology in Norway. The rollout of the Metavision, iMDsoft eMAR and BCMA system spanned three years, from 2017 to 2019. The system encompassed digital medication records, barcode scanners, patient identification (ID) wristbands, single-dose medication units, and barcode scanning protocols for both dispensing and administration stages. The hospital utilized a decentralized, ward-based medication dispensing system. The detailed dispensing and administration process, along with corresponding policy descriptions, is visually represented in figure 1. Data collection took place on two distinct wards: a cardiac medical ward and a geriatric intensive care ward. Additional details regarding ward characteristics and observation periods are available in online supplemental appendix 1.

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Process flow for medication dispensing and administration with BCMA. This diagram illustrates the steps involved in the BCMA process, from medication order to administration, highlighting key points where barcode scanning is intended to enhance safety and accuracy.

Supplementary data: bmjqs-2021-013223supp001.pdf

Defining Policy Deviations

For the purpose of this study, a policy deviation was defined as any instance where medication dispensing or administration did not adhere to established hospital policies. Specific categories of deviations were defined as follows:

- Task-related deviations: Failures or omissions related to barcode scanning tasks during dispensing and administration.

- Organizational policy deviations: Violations of hospital medication management policies, such as dispensing incorrect medication doses into the patient drawer on the Computer on Wheels (COW).

- Technology-related factors: Issues arising from the technological equipment (hardware and software) associated with BCMA that led to deviations.

- Environmental factors: Aspects of the physical environment that negatively impacted BCMA usage and contributed to deviations.

- Nurse-related factors: Practices or comments from individual nurses that indicated deviations or influenced BCMA usage.

Data Collection Procedures

Data collection was conducted by a registered pharmacist and a fifth-year pharmacy student during medication administration rounds between October 2019 and January 2020. Prior to each observation session, observers contacted the assigned nurse, explained the study’s purpose, and obtained informed written consent. Upon entering a patient’s room, the nurse briefly informed the patient about the observer’s presence and the study’s objective. To minimize observer bias,21 observers maintained a silent, non-interactive role throughout the observation period. No patient-identifiable information was recorded. Observers were instructed to intervene only if they detected a medication error with the potential to cause immediate patient harm.

A digital observational tool (detailed below) was used to collect quantitative data, with data consistency regularly checked by the research team. Data were captured using handheld tablets and securely transmitted to a protected server. Following each structured observation, observers documented qualitative field notes detailing the medication safety environment and any relevant comments made by the nurses.

Data collection continued until data saturation was reached, determined by the research team’s assessment that additional data would not yield new significant insights.22 Regular meetings were held between observers and the research team to review collected data and assess saturation.

Development and Piloting of the Digital Data Collection Tool

A custom digital observational tool was developed using secure web-based data survey software23 to facilitate data collection during medication administration. This tool was rigorously piloted for seven days by two observers, who observed medication administration for 30 patients across two medical wards. While pilot data were not included in the main study analysis, they were thoroughly reviewed by an inter-professional research team. Each question within the observational tool was evaluated for its relevance to the research questions and alignment with current evidence-based practices. Separate data collection tools were developed for oral and parenteral medications to accommodate the distinct processes involved in their administration (online supplemental appendices 2 and 3). The 28 questions across both tools (14 in each) were designed to align with hospital medication administration policies and quantify data on:

Supplementary data: bmjqs-2021-013223supp002.pdf

Supplementary data: bmjqs-2021-013223supp003.pdf

- Total medications administered; number of scannable and scanned medications; number of scanned patient ID wristbands.

- Policy deviations related to dispensing, labeling, storage, and scanning.

- Technological issues with hardware or software.

- Storage practices for patients’ own medications brought from home.

- A free-text field was included in the tool for observers to record additional comments and contextual notes.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data from both observational tools were combined, and string data were converted to numerical values for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze scanning rates and the frequency of policy deviations using IBM SPSS V.25. Qualitative data, including field notes and nurses’ comments, were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis24 through an iterative process. Two researchers independently coded the data, assigning utterances to emergent themes. The researchers then discussed and refined theme interpretations to reach a consensus. Following separate quantitative and qualitative data analyses, the two datasets were integrated using a triangulated approach.25 26 Key findings from both datasets were identified, and complementary findings were compared to enhance the validity and depth of understanding of policy deviations and their underlying causes. Integrated findings were subsequently categorized according to the five elements of the SEIPS model.20

Results

Observations were conducted on 44 nurses administering medications, with 29 observed during morning rounds and 15 during evening rounds. A total of 884 medications (average 4.2 per patient, range 0-14) were administered to 213 patients (table 1). Of these patients, 133 (62%) received only oral medications, 59 (28%) received both oral and parenteral medications, and 21 (10%) received only parenteral medications.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Observed Barcode Medication Administration

| Characteristics | Ward 1 | Ward 2 | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observation duration | 14 hours 35 min | 17 hours 48 min | 32 hours 23 min |

| Number of observed nurses | 22 (21 female; 1 male) | 22 female | 44 |

| Number of observed medication rounds | 18 (12 at 8:00; 6 at 20:00) | 20 (14 at 8:00; 6 at 20:00) | 38 |

| Total number of observed patients | 94 | 119 | 213 (100%) |

| Number of patients with scanned wristband | 85 | 85 | 170 (80%) |

| Total number of medications | 447 | 437 | 884 (100%) |

| Number of barcoded medications | 373 | 315 | 688 (78%) |

| Number of scanned medications | 319 | 306 | 625 (71%) |

Task-Related Policy Deviations

Quantitative Data: Observational Tool

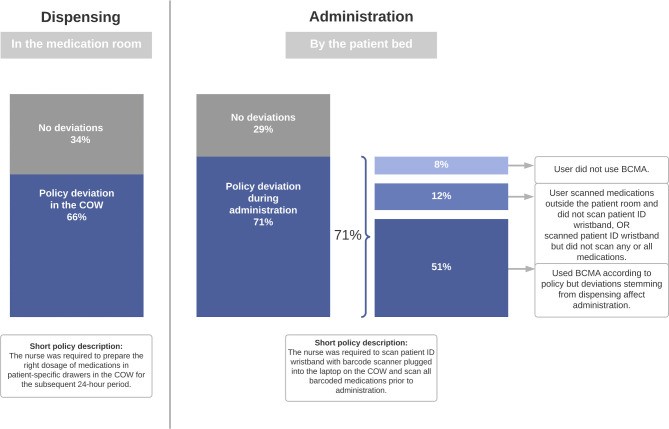

Data from the observational tool revealed significant task-related policy deviations in BCMA usage. During medication dispensing, deviations affected 140 patients (66%), and during medication administration, 152 patients (71%) experienced task-related deviations, as illustrated in figure 2. Analysis of administration practices identified three primary variations in nurses’ BCMA use that resulted in deviations: complete non-use of BCMA, partial BCMA utilization, and correct BCMA use where deviations still occurred due to system factors.

Figure 2.

Figure 2: Breakdown of task-related policy deviations observed during barcode medication administration. This chart visually compares deviation types in dispensing and administration phases, emphasizing areas for process improvement.

Organizational Policy Deviations

Data Synthesis: Observational Tool, Field Notes, and Nurse Comments

Organizational policy deviations, defined as departures from established medication management policies, were also prevalent. Notably, 29% of medications and 20% of patient ID wristbands were not scanned during administration (table 1).

Ten distinct types of policy deviations were identified during the medication dispensing process. The most frequent were medications not dispensed (n=80 patients), missing barcode labels (n=70 patients), and incorrect dose dispensed (n=30 patients). Dispensing deviations and their potential links to medication errors are detailed in table 2. It is important to note that while all entries in table 2 are categorized as deviations, three also constitute actual medication errors: wrong medication dispensed, wrong dose dispensed, and medication not dispensed and not administered (medication omission). These dispensing errors, often discovered after nurses entered patient rooms, led to prolonged and frequently interrupted administration processes, contributing to medication omission for 25 patients. In 11 instances, the BCMA system’s scanning function effectively prevented the administration of incorrectly dispensed medications. In one critical instance, an observer intervened when a nurse mistakenly dispensed a look-alike medication from the medication room and intended to administer it to a patient.

Table 2.

Organizational Policy Deviations in Barcode Medication Administration and Potential Medication Error Links

| Types of policy deviations* | N | Examples and descriptions | Potential medication errors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medication not dispensed; obtained and given during observation | 55 | Nurse did not check for omission of dispensing before administration round start even though some medications (eg, parenteral injectables) were not expected to be found in the COW at all | Omission |

| Medication not dispensed; not given during observation† | 25 | Omission | |

| Barcode label missing | 70 | Dispensed tablets without a barcode label, or without primary packaging | Wrong medication, Wrong dose |

| Wrong dose dispensed† | 30 | Dispensed whole blister pack instead of one tablet (correct dose) | Wrong dose |

| Scanning failure | 26 | Barcode on the medication was not readable for the scanner | Wrong medication, Wrong dose, Wrong route |

| Barcode label not attached | 13 | Barcode label was in the patient drawer but not attached to the medication; Nurses stored expired labels for future administrations to save time from printing new labels | Wrong medication |

| Wrong medication dispensed† | 11 | Dispensed extended-release tablet instead of tablet; Dispensed sound-alike medication, for example, Lescol instead of Losec; Dispensed 2 g Cloxacillin intravenous bag from the storage room instead of 1 g; Errors discovered by scanning in eMAR | Wrong medication |

| COW deviations due to recent changes in the eMAR | 7 | Antithrombotic medication was dispensed in the patient drawer, nurse removed it during administration due to the patient being scheduled for surgery that day | Contraindication, Wrong drug, Wrong route |

| Medication placed in the wrong compartment in the drawer | 5 | During dispensing, medication prescribed for morning administration was placed in the compartment in the patient drawer assigned for evening administration | Wrong medication, Omission or wrong time |

| Wrong room number on patient drawer | 3 | The patient changed the room, but the room number on the patient drawer was not changed | Wrong patient |

| Wrong label attached | 1 | Attached ‘metoprolol’ label on a generic substitute Bloxazoc (metoprolol) unit dose. Revealed after failure with scanning the label | Wrong medication, Wrong dose |

| Patients’ own medication stored in the patient room | 24 | We observed deviation of this policy for 24 of total 25 patients’ own medications (96%) | Wrong dose, Wrong medication |

*The number of deviations refers to one deviation of the same type per patient even if more deviations of same type exist with one patient, for example, if one patient had wrong dose dispensed for two medications, this was counted as one deviation.

†Deviations which also classify as actual medication errors.

Deviations related to the storage of patients’ own medications (brought from home) were also frequently observed. Hospital policy dictated that these medications should be stored within the COW or medication room. However, a 96% deviation rate was recorded for this policy (table 2). Patient-owned medications were not integrated into the BCMA system, thus were neither barcoded nor scanned.

Technology-Related Factors

Data Synthesis: Observational Tool and Field Notes

Technology-related factors contributed to policy deviations in 38 observations (18%). These included prevalent issues with low laptop battery in 28 observations (13%), system freezes in seven observations (3%), malfunctioning barcode scanners in two observations, and scanner unavailability for administration in one observation (online supplemental appendix 4). Software problems included slow system response and the need for excessive clicking after each medication scan, which nurses found frustrating when using the laptop mousepad for eMAR navigation. The physical dimensions of the COW were also considered a hindrance, slowing down the administration process and contributing to deviations.

Supplementary data: bmjqs-2021-013223supp004.pdf

Environmental Factors

Data Synthesis: Observational Tool, Field Notes, and Nurse Comments

The physical location of medication rooms, situated at a distance from nursing stations and patient rooms, emerged as a significant environmental factor. Nurses frequently had to travel back and forth to the medication room during administration rounds to rectify dispensing deviations in the COW. Another disruptive environmental factor was the insufficient size of patient drawers in the COWs, which could not accommodate all necessary patient medications. Untidy work surfaces on COWs and nursing stations, often cluttered with single-dose medication units from previous administrations or incorrectly dispensed medications, also contributed to workflow disruptions.

Nurse-Related Factors

Data Synthesis: Observational Tool, Field Notes, and Nurse Comments

Several nurses admitted to infrequent use of the barcode scanning equipment in their daily practice. During periods of high ward workload, nurses tended to bypass BCMA, perceiving it as a slowdown to medication administration. Conversely, nurses who regularly utilized BCMA recognized and valued the automated medication verification process as a safeguard, ensuring patients received the correct medications.

Root Causes of BCMA Policy Deviations

Table 3 summarizes the probable causes of BCMA policy deviations, categorized according to the SEIPS model elements and linked to data sources. Task-related deviations, such as failure to scan medications during administration, often stemmed from the initial omission of scanning during dispensing. A non-streamlined workflow during administration was frequently attributed to a mismatch between BCMA task requirements and the actual workflow demands. Organizational deviations were largely caused by unclear or inadequately communicated policies, lack of policy awareness among healthcare professionals, or policies incompatible with efficient workflow. Even in cases where policies were clear and prescriptive, deviations persisted; for example, despite policies mandating dispensing only the prescribed dose, whole tablet blisters were occasionally dispensed in the COW.

Table 3.

Probable Causes of Barcode Medication Administration Policy Deviations According to SEIPS Categories

| Probable cause | Example from observation/description | Data source |

|---|---|---|

| Tasks related | ||

| Scanning discarded during dispensing | Medications dispensed without scanning in the eMAR failed to scan during administration | Observational tool |

| Workflow not adopted to required tasks during administration | Nurse makes multiple runs back and forth to the medication room to retrieve not dispensed medications which interrupts the workflow and may affect patient safety | Observational tool, Nurses’ comments |

| Suboptimal task performance | Voluminous medications (such as infusion bags, inhalers, eye drops) are routinely not scanned during dispensing because they are retrieved during administration | Observational tool, Nurses’ comments |

| Organizational | ||

| Dispensing practices not adopted to nurse’s workload, resulted in normalising deviations | Manual labelling of medications during dispensing on ward was challenging to carry out without workarounds | Observational tool |

| Non-standardized dispensing process resulted in frequent deviations | Medication not barcode labelled; scanning failure; wrong dose dispensed; wrong medication dispensed; medication not dispensed; wrong label attached | Observational tool |

| Unclear procedures or task not assigned | Varying practice between the wards on updating the dispensed medications in the COW due to recent changes in the eMAR | Observational tool, Nurses’ comments, Field notes |

| Poor routines/not followed routines for changing the room number on patient drawer | Room number on patient drawer was another patient’s room number (Each patient drawer was labelled with room number and this was the first step in identifying the patient’s medications) | Observational tool |

| Unaware of hospital policies | Patient’s own medications stored in the patient room. Due to policy, patients’ own medication should be stored in the COW or the medication room | Observational tool |

| Technology | ||

| Poor charging routines or non-compliance with routine | The laptop battery was low either at the start or during administration | Observational tool |

| eMAR usability issues | Slow eMAR response and need for multiple clicking after scanning each medication | Field notes |

| The scanners were not wireless and limited the patient ID scanning | Nurse scanned medications prior to entering the patient room and administered medications while the COW was in the hallway, meaning that the patient ID wristband was not scanned | Field notes |

| Suboptimal COW design | Nurses often avoided to bring the bulky COW into the patient room when administering few or one single medication; The COW design was cumbersome for the desired workflow of entering patient rooms during administration rounds; The COW contained medications for all patients which combined with scanning not being used is a risk for patient safety | Field notes, Nurses’ comments |

| Environmental | ||

| Medication room location affects task efficiency and time spent administering medications | The medication room was located far from the nursing station and most of the patient rooms. This resulted in slower administration and storage of random medications in the nursing station to avoid going back and forth to the medication room | Observational tool, Field notes |

| Patient drawer size does not allow appropriate BCMA use | The small size patient drawer led to deviations such as not dispensing the medications because only small forms of oral medications and ampoules were dispensed in the patient drawer, whereas voluminous medications were retrieved during administration | Observational tool, Field notes, Nurses’ comments |

| Non-specific medication storage policy | Random single-unit doses stored on the desk in the nursing station or on the COWs and were obtained from here in case something was missing during administration. Unsafe practice as the single doses are easy to mix up when stored randomly on the COW during administration | Field notes |

| Nurse related | ||

| Non-standardized dispensing allows variations | Variations in performance between nurses and inconsistency in dispensing medications for the same nurse | Observational tool, Field notes, Nurses’ comments |

| BCMA slower than manual verification—leading to user dissatisfaction | Nurse did not use the BCMA at all during the whole medication round; Nurse admitted to not using the BCMA on regular basis but used it during observation period | Observational tool, Field notes, Nurses’ comments |

Probable causes for technology-related deviations included inadequate charging routines, non-wireless scanners tethered to laptops, and software usability issues. The bulky design of the COW and non-wireless scanners frequently prevented nurses from scanning patient ID wristbands at the bedside. The undersized patient drawers contributed to dispensing omissions due to insufficient space for all medication types. Nurse-related deviations were often attributed to the perceived slowness of the BCMA process, leading to nurses bypassing scanning procedures or entirely omitting technology use. These factors collectively compromised patient safety during medication dispensing and administration.

Discussion

This study revealed a high prevalence of policy deviations, affecting a significant majority of patients during both medication dispensing (6 out of 10) and administration (7 out of 10). The root causes were multifaceted, encompassing a complex dispensing process, slow or cumbersome BCMA procedures, suboptimal technology design, and ambiguously defined policies. The demanding workload and system inefficiencies created an environment where policy deviations became normalized practices.

Despite these systemic challenges, the study highlights the potential safety benefits of BCMA. When medication and wristband scanning were consistently implemented, the system effectively prevented the administration of incorrectly dispensed medications in 5% of patient cases, demonstrating a crucial safety net.

The observed lack of standardized dose delivery led to inconsistencies in medication dispensing within the COW. While BCMA is intended to enhance predictability and error detection, as noted by Patterson et al 27, the uncertainty surrounding dispensed medication accuracy in this study forced nurses to manually re-verify doses before administration, undermining BCMA’s intended efficiency and error-reduction benefits.

The study’s scanning rates—71% for medications, 91% for scannable doses, and 80% for patient ID wristbands—fall considerably short of the recommended 95% benchmark for medication and patient scanning.28 Comparatively, a recent observational study in a UK hospital by Barakat and Franklin reported higher scanning rates for medications (83%), scannable doses (95%), and patient verification (100%).29 Although their study had a smaller sample size, similar ward-stock dispensing processes and BCMA technology designs suggest comparability between the two settings.

National data from Norway, where BCMA is not universally implemented, indicate that 70% of medication errors occur during the administration phase.3 This underscores the potential of BCMA to mitigate administration errors, such as wrong dose, wrong patient, and wrong medication. However, even with accurate technology utilization, the study demonstrates that hospitals may not fully realize BCMA’s safety benefits and may encounter unintended consequences,18 as evidenced by the current findings. In this study, intended BCMA use occurred in only approximately half of medication administrations. Deviations often originated in the dispensing process (e.g., non-dispensed medications, wrong medication/dose dispensed), leading to subsequent deviations even when BCMA was correctly used during administration.

Reliable hardware functionality is paramount for BCMA’s error-preventive efficacy. While recurring issues like uncharged laptops and scanner borrowing were observed, the study identified technology design limitations, such as the bulky COW and non-wireless scanners, as more significant contributors to deviations. These design issues hindered staff efficiency during medication administration, potentially explaining the 20% non-scanning rate of patient ID wristbands. The cumbersome size of medication carts obstructing efficient BCMA use has been previously documented.4 18 One study even found that nurses perceived manual patient identity verification as faster than maneuvering large medication carts into patient rooms.27

The distant location of medication rooms indirectly compromised patient safety. The time-consuming process of retrieving missing medications from the COW contributed to medication omissions. Additionally, environmental factors, such as undersized patient drawers preventing dispensing of larger medications (e.g., eyedrops, inhalers, syringes), directly conflicted with medication safety, echoing findings from other studies.30

Nurses in this study also reported that BCMA increased medication administration time. In contrast to settings with automated dispensing cabinets18 or pharmacy-operated dispensing,12 nurses in this ward-based system had more dispensing-related tasks (e.g., packaging, labeling, drawer compartment dispensing), likely contributing to the higher proportion of dispensing deviations observed.

This study reveals variability in nurses’ BCMA utilization, ranging from complete non-use to full compliance. Much of this variability can be attributed to factors like missing medication barcodes and workflow-permitting policy variations. In contrast, Barakat and Franklin’s study found that BCMA reduced variability in medication administration practices.29 These differences may reflect variations in safety culture. If BCMA technology is not universally adopted, as seen in this study, it can become a workflow burden rather than a safety asset. Lyons et al 31 similarly described performance variability among nurses using other medication administration technologies, suggesting that adaptive behavior can be a source of system resilience but also a potential source of suboptimal outcomes.

Implications for Improving BCMA Implementation

This in-situ study of BCMA use offers valuable insights for technology implementation and improvement strategies:

- Pre-Implementation Risk Assessment: Hospitals should proactively risk-assess policies before BCMA implementation, making institution-specific decisions on integrating technology into existing workflows.

- Enhance Medication Scannability: Increasing the proportion of scannable medications, potentially through pharmaceutical industry adoption of primary packaging barcoding,32 could reduce nursing workload and standardize dispensing processes across wards.

- Ward-Based Dispensing System Evaluation: The efficiency and safety of ward-based medication dispensing, linked to higher medication error rates compared to unit-dose systems,33 should be critically evaluated.

- Technology Redesign for Workflow Compatibility: Redesigning technology to better align with nursing workflows, such as replacing bulky COWs with lightweight carts and mobile eMAR devices, could improve user experience and mitigate current system drawbacks.

- Usability and Functionality Enhancements: Greater attention to BCMA usability and functionality is crucial. The absence of override logs and scanning statistics in the studied BCMA system significantly limits technology use monitoring.

- Ongoing Assessment and End-User Involvement: Beyond data monitoring, regular assessments of actual BCMA use, such as periodic medication round observations,13 34, are essential. Engaging end-users in improvement suggestions is also vital.

- Inter-Hospital Knowledge Sharing: Facilitating shared learning of BCMA best practices among hospitals with similar systems is an important resource for knowledge dissemination, implementation refinement, and staff motivation.

Strengths and Limitations

The mixed-method approach is a key strength, providing rich insights into nurses’ BCMA use and the contextual factors driving policy deviations. The integration of qualitative and quantitative data allowed for identifying both the frequency of deviations and their underlying causes. The observational tool effectively detected ‘normalized’ deviations (e.g., wrong dose dispensing) that often remain hidden using standard incident reporting methods.35 While previous studies have demonstrated BCMA’s potential to reduce medication error rates,4 5 7 8 this study highlights how policy deviations can create latent system flaws that could ultimately lead to serious medication errors. However, the focus on policy deviations, rather than direct medication error measurement, is a limitation in directly quantifying BCMA’s impact on patient safety.

Further limitations include potential observer variability in data collection and interpretation, despite rigorous observer training36–38 and policy familiarization. The observer effect, where nurses may modify behavior due to observation,39 is also acknowledged. However, any behavioral changes were expected to be towards improved BCMA compliance. Medication dispensing observations, occurring before direct observation periods, were less susceptible to this bias.

The study’s focus on an eMAR-BCMA system within a ward-based medication dispensing hospital limits generalizability to organizations using pharmacy-operated or automated dispensing systems. Conversely, hospitals employing ward-based dispensing systems can particularly benefit from these findings, as research in this context is limited.

Conclusion

This study provides a detailed understanding of BCMA use in a real-world clinical setting. A significant proportion of observations revealed policy deviations, including non-scanning of patients and medications, dispensing omissions, and incorrect dose dispensing. Variations in nurses’ BCMA practices were also evident. Deviations were driven by unclear policies, policies hindering proper BCMA use (including labor-intensive dispensing), and technology design flaws. The findings underscore the need for work system reassessment and adaptation to better align with nurses’ workflows. Policy deviations are inherent in complex technology implementations. Analyzing these deviations in practice is crucial for identifying and addressing system weaknesses to fully realize BCMA’s patient safety benefits.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the nursing staff for their participation in this study. They also acknowledge the contributions of staff from the Southern and Eastern Norway Pharmaceutical Trust and the Department of Information and Communication Technology at the hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: AM and AGG conceptualized the study. KT, LM, and AGG contributed to planning and supervision. AM led data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was internally funded.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: Additional content provided by the authors, not vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ). BMJ disclaims liability for reliance on this content.

Data availability statement

Data are unavailable due to participant confidentiality agreements.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Approved by the institutional data protection board.

References

[List of references as in the original article]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data: bmjqs-2021-013223supp001.pdf

Supplementary data: bmjqs-2021-013223supp002.pdf

Supplementary data: bmjqs-2021-013223supp003.pdf

Supplementary data: bmjqs-2021-013223supp004.pdf

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to participant confidentiality agreements.